Directed by Masahiro Makino

In a departure from his upright samurai detective character the Bored Hatamoto, Utaemon Ichikawa is on the wrong side of the law this time around. I’m not sure which crimes he’s supposed to be guilty of. He refers to himself as a shady racketeer. All I know is that Utaemon has so much swag in this movie that it ought to be illegal.

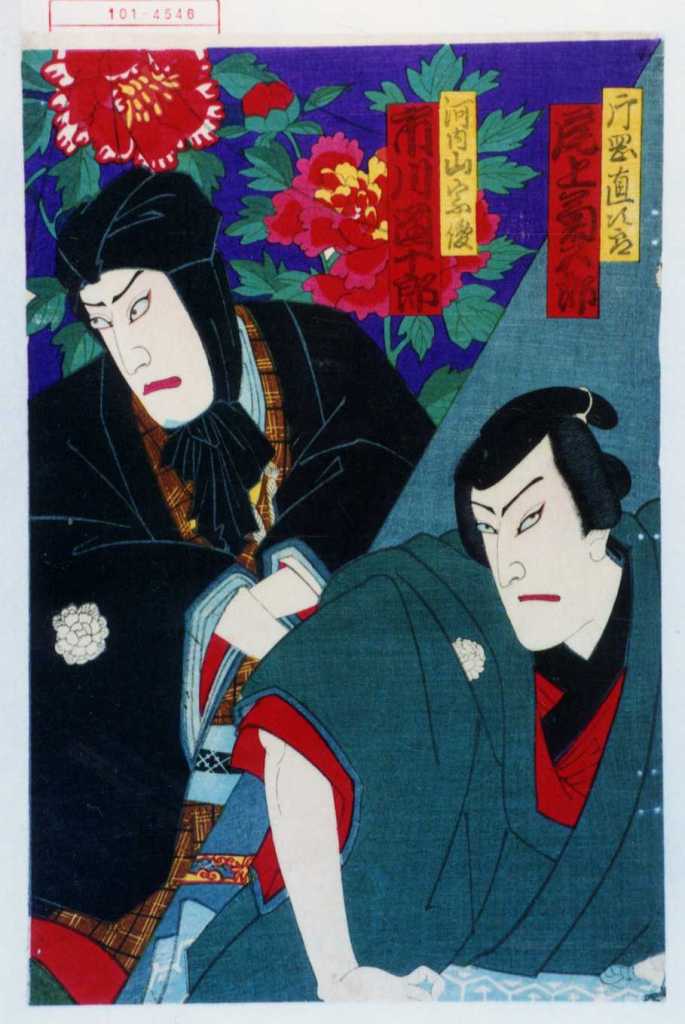

Utaemon plays Kōchiyama Sōshun, the 19th century outlaw. The film is based upon a novel by Kan Shimozawa, the creator of Zatoichi, the blind swordsman. Tenpō Rokkasen – Jigoku no Hanamichi is Masahiro Makino’s second adaptation of Kōchiyama Sōshun’s story, the first being a black and white feature he made for Daiei in 1952. Kōchiyama is also a character in a famous Kabuki play, Kumo ni Magō Ueno no Hatsuhana. (It’s usually referred to simply as Kōchiyama.) The play in turn derives from a traditional Japanese form of oral history/storytelling called kōdan.

Kōchiyama is essentially a gangster. He describes himself as the scum of the earth. In addition to his illicit activities Kōchiyama is also a priest and a palace aide. As such he has plenty of dirt on people in high places, and he can fake being upper class if he needs to. This will come in handy later.

The film opens in an Edo bathhouse where Kōchiyama is relaxing. A samurai (Chiyonosuke Azuma) enters. He’s being chased and looking for a place to hide. Kōchiyama directs him to the ladies’ bath next door. In the ladies’ bath is Kōchiyama’s girlfriend Ogin. She is played by Chikage Awashima whom we last saw in Ishin no kagaribi as Chiezō Kataoka’s girlfriend, and once again she has got herself into a relationship with a man unable to commit. On the plus side, Kōchiyama’s more fun than the rather strait-laced Vice Commander of the Shinsengumi, and makes appreciative comments about her ass.

A group of samurai descend upon the bathhouse. The ruse works, and the fugitive samurai survives his embarrassing stay in the women’s bath. We will meet him again shortly.

Kōchiyama has taken a young man under his wing: Naojirō (Nakamura Katsuo).1 Despite his cherubic face Nao’s a venal thug. Whenever he’s not roughing people up and extorting money from them Nao spends his time chasing the courtesan Michitose (Satomi Oka), who is young enough and silly enough to be in love with him. Kōchiyama is trying to find out more information about Michitose’s background at the behest of his brother Moritaya (Jūshirō Konoe), who has reason to believe that Michitose is his long-lost sister. Moritaya intends to rescue her and buy out Michitose’s contract at the brothel. But her relationship with Naojirō presents an obstacle.

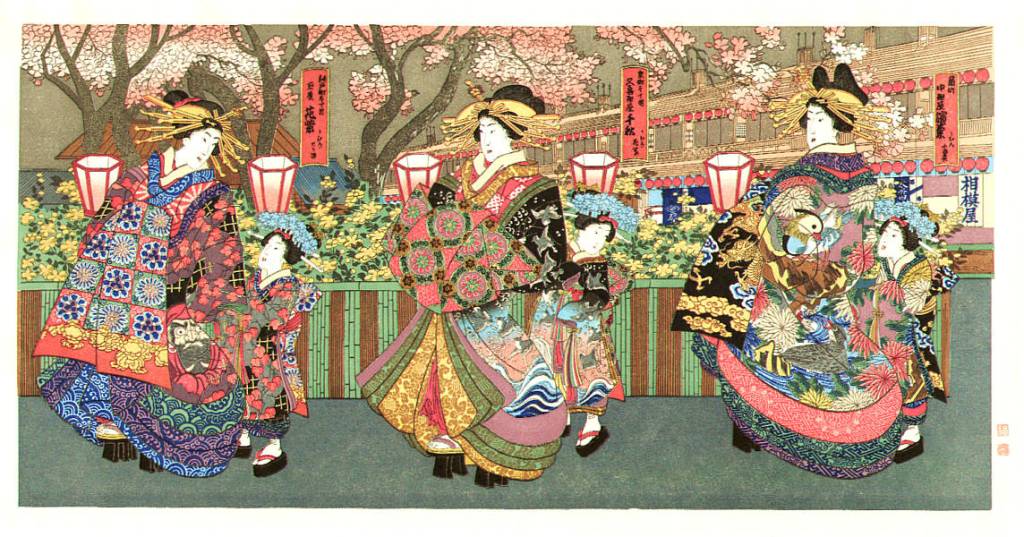

Kaneko, the samurai from the bathhouse, visits Kōchiyama to request his help. Kaneko’s father was killed after being accused of embezzling funds that belonged to the shogunate. The samurai who are after him wish to stop anyone looking into what happened to the money. Kaneko is determined to clear his father’s name and avenge his death. Kōchiyama agrees to assist Kaneko with his vendetta but has a hidden agenda: he wants to get Michitose away from Nao. He arranges for Kaneko to visit Michitose in Yoshiwara, Edo’s red-light district.

Kaneko is mortified. He has never been to a brothel. He doesn’t drink or smoke either. “This is hopeless,” Michitose says, exasperated. Clearly out of his element, Kaneko makes his excuses and leaves. Nao arrives and hooks up with Michitose. Kōchiyama’s plan has backfired, and he’s pissed off.

Kaneko is ambushed on his way home by samurai from the Matsue clan who were hunting him earlier. Kōchiyama happens upon the fray in progress. Now he’s really pissed. “No one bloodies the streets of the shogun’s own city,” Kōchiyama growls at them, which sounds like something the Bored Hatamoto would say. “You bastards!” After perforating a few of the aforementioned bastards with his sword Kōchiyama is game to take the whole crew on, but they flee into the darkness.

Ogin has stayed up all night waiting for him. She appears to have been drinking. “I do love you,” Kōchiyama confesses, and I believe he means it. Ogin shoots back, tearfully: “Liar!” She falls into his arms. He’s tempted but doesn’t want to take advantage of Ogin’s intoxicated state. Kōchiyama puts her to bed and leaves.

Kōchiyama can’t resist a high-stakes gamble and comes up with a risky plan to expose the men who framed Kaneko’s father. The highlight of the film, as in the play, is Kōchiyama’s infiltration of Lord Matsue’s palace disguised as Kitadani no Dōkai, a priest from Kan’eiji temple. He almost pulls it off. Just as Kōchiyama is about to make his exit, samurai from the ambush that took place the other night recognize him. Kōchiyama goes for broke. He drops the act and scares the hell out of everybody.

Having obtained an undertaking from Lord Matsue to investigate the embezzling incident and thereby cleared up part of Kaneko’s predicament for him, Kōchiyama warns Kaneko: “I don’t do anything for free. I’ll come to you one day to collect.” He’s running out of time: Kōchiyama is a wanted man now for impersonating a high-ranking priest, a capital offense.

Kōchiyama is about to learn that crime does not pay, and the film takes a darker turn. There’s not a ton of sword fighting in this, but Utaemon is always a pleasure to watch when he gets going. He’s like an undammed river: if you want to survive, your only option is to move out of the way.

Kōchiyama meets his fate like a boss in the film’s theatrical finale. Utaemon also has a great scene in which Kōchiyama tells off the prissy samurai for refusing to have Michitose join his household as a servant because she’s a whore.

On that note I would add that the one thing I take issue with is the film’s sanitized depiction of prostitution. Look, I get it. Kōchiyama’s a criminal. Most of his associates in the movie are criminals or otherwise living on the margins of Edo society in the 19th century. It would be unrealistic to expect any of these characters to exhibit a more enlightened attitude. Consider it a sin of omission rather than commission on the filmmakers’ part.

Yoshiwara appears in ukiyo-e, Kabuki plays, and Japanese historical dramas quite often, which makes it ideal subject matter for this blog. A film in my queue of movies awaiting review is one of the harshest indictments of prostitution I’ve ever seen, and it was released in 1959. That’s a year before this movie.

- Nakamura Katsuo (b. 1938) who plays Naojirō is the younger brother of Nakamura Kinnosuke and like him has a Kabuki background. You may recall Katsuo as the blind musician in Toho’s classic 1964 horror anthology Kwaidan. ↩︎

Leave a comment