Directed by Sadao Yamanaka

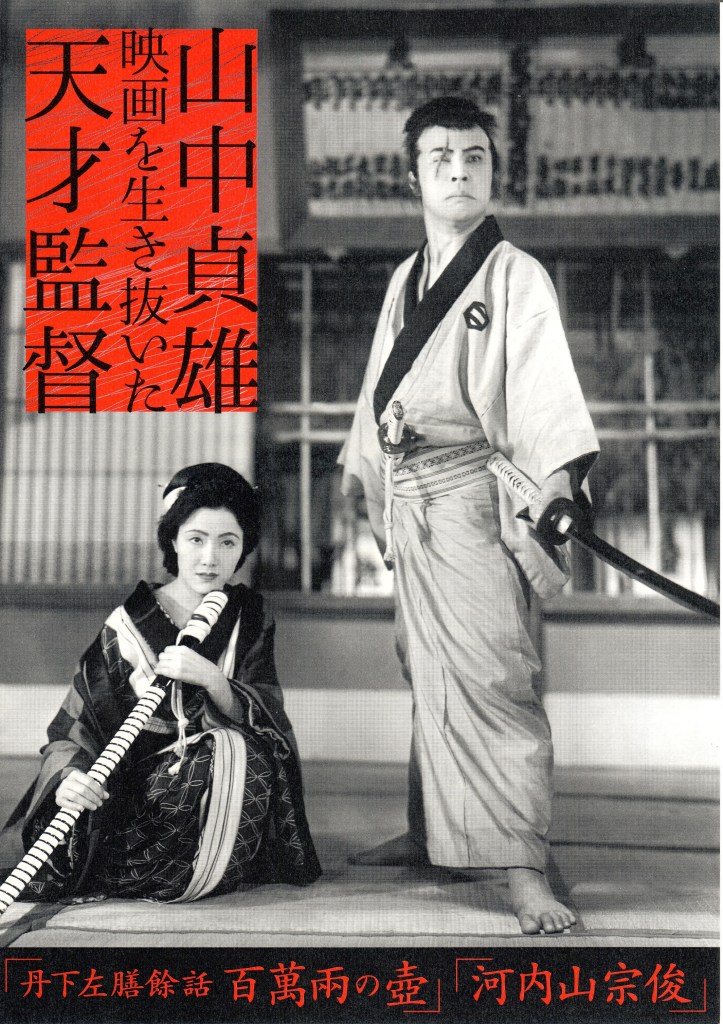

I’m delighted to say that today’s film has no shortage of reviews online. Unlike my blog’s usual fare, it’s a comedy. I tend to avoid reviewing comedies from other countries because appreciating humor typically requires a high degree of cultural context and linguistic fluency, but this movie is irresistible. In fact I loved it so much I bought the poster:

© Nikkatsu

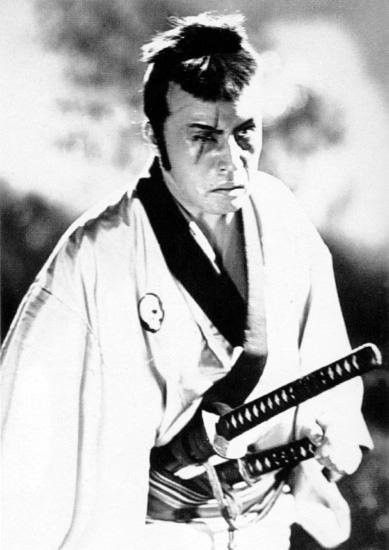

That’s the great jidaigeki actor Denjirō Ōkōchi in his signature role as the disabled samurai Tange Sazen. Other actors have played Tange Sazen but Denjirō owns this part. As Sazen he scowls a lot:

He has a killer smile, though, and he’s really rather attractive, scar and all:

© 1939 Toho Co., Ltd

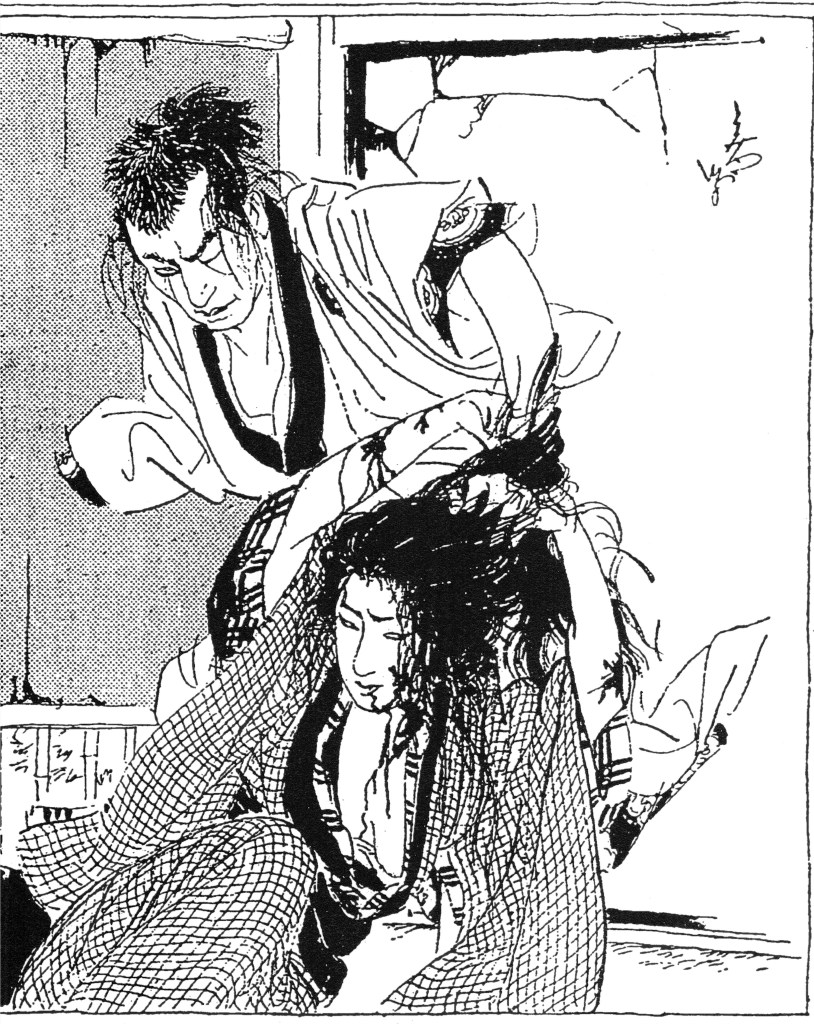

Yamanaka’s film changed Tange Sazen from a lone wolf rōnin into a more pro-social character. He still kills people, but only if they deserve it. A Tange Sazen movie in which Sazen spends most of his time grumbling and hanging out with his girlfriend Ofuji (Shinbashi Kiyozō) instead of sword fighting is funny of itself, and the film really runs with this. I like that we get to know Sazen as a person and not just a swordsman, although no details are given about how Sazen became disabled. That story is too tragic for a light-hearted film. Tange Sazen’s creator Kaitarō Hasegawa (writing under the pen name Hayashi Fubō) objected to the liberties Yamanaka took with his character. In the books Sazen is not exactly warm and cuddly as you can see here:

The film’s set-up involves the search for an antique pot decorated with a map to a million ryō treasure. The pot eventually finds its way into the house Sazen shares with Ofuji and a young orphan boy whom they have informally adopted. One of the film’s charms is that you think you know where it’s going, but it takes a detour and ends up somewhere unexpected. Another is the unique atmosphere of the indoor archery arcade/bar where much of the movie takes place. Ofuji is its shamisen-playing proprietress and Sazen works as the bouncer.

© Nikkatsu

The place has such a chill vibe that his services are rarely needed. When they are, Sazen springs into action.

© Nikkatsu

Sazen and Ofuji have a strong relationship. Sazen is embarrassed that he has to rely on Ofuji for money but both do what they can to support one another. In terms of temperament they’re well matched. He’s irascible; she is cool and self-possessed. They bicker and tease each other. This is contrasted with the loveless arranged marriage of the aristocratic Gensaburo (Sawamura Kunitaro IV). Gensaburo, who received the eponymous pot as a wedding gift only to have his bride sell it to a junk shop, is completely hen-pecked and would rather flirt with girls at the archery bar than stay at home with his wife whom he doesn’t even seem to like. By the end of the film a million ryō doesn’t seem all that tempting, and life at Ofuji and Sazen’s place goes on much the same as before.

The highlight for me is Sazen’s furious storming of Gensaburo’s dōjō. Not only is it very funny, but it provides the perfect opportunity for Denjirō to show off Sazen’s distinctive fighting style. Tange Sazen lost his right arm in a traumatic amputation and had to learn how to fight with his left. His disability actually gives him an edge: Sazen beats every single right-handed fencer easily. With left-handed people comprising just ten percent of the population (and probably less than that during the period in which the film is set due to cultural factors mitigating against left-handedness) few swordsmen would have ever encountered a lefty combatant. As a southpaw myself I can only applaud Sazen’s magnificent badassery.

There are prints of varying quality on YouTube. The print on the Internet Archive is in pretty good shape but it’s missing a fight scene. This scene was cut at the behest of the Civil Censorship Detachment, who imposed a sweeping ban on all sword-fighting scenes during the postwar Allied occupation of Japan. (You can imagine the impact this ban had upon the careers of actors and other creative artists who made their living producing period dramas.) A fragment of the censored sequence survived and is incorporated into the digitally restored version with English subtitles, which can be seen here.

It’s almost incredible that such a smart and deftly crafted movie was the work of a 26 year-old. Sadao Yamanaka’s career was tragically cut short after he was drafted into the Imperial Army. His death at age 28 deprived cinema of one of its most brilliant young directors. Only three of Yamanaka’s 28 films survive in complete form, and each is now considered an undisputed classic. His final film Ninjō kami fūsen (Humanity and Paper Balloons) is available on the Criterion Channel.

I hope that Criterion will acquire the rights to the restored version of Tange Sazen and the Pot Worth a Million Ryō because if any film deserves the full Criterion treatment, it’s this.

© Nikkatsu

Leave a comment