Directed by Norifumi Suzuki

(Clean Draft of a Love Letter, or Pure Drawings of Female Beauty)

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution –

Non-Commercial – ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Look, I know. I KNOW.

Hear me out. This is a good movie!

I’m struggling to describe it. It’s… a soft-core dramedy? The title character is an absurd figure played with admirably straight-faced conviction by Hiroshi Nawa. I have to admit it feels weird to me as a Western viewer to see legit actors appearing in this sort of film. While the premise is silly and much of the content is Not Safe for Work, the production values are excellent, and the direction is insanely assured.

Director Norifumi Suzuki is noted for his 1970s action comedy series Torakku Yarō (Truck Guys) for Toei and exploitation films like Terrifying Girls’ High School: Women’s Violent Classroom, which based upon its title I assume is a documentary about my high school. It was a Catholic girls’ school and I had a particularly hard time. Shy and unpopular, I was bullied without mercy. One of the few bright spots in this purgatorial experience was a course on Non-Western Cultures. The segment on Japan was taught by Ms. Duff. She not only spoke Japanese fluently but could read and write it as well. Ms. Duff was a very cool person and a gifted teacher. I was enchanted by a film she showed us depicting Kabuki and bunraku, the traditional Japanese puppet theatre with its beautiful puppets and mysterious spectral figures dressed in black operating them.

I absolutely loved the entire course and to this day remain grateful to have had such a wonderful teacher as my first guide to Japanese culture. I doubt that Ms. Duff or any of my teachers would be pleased to see me writing about a Japanese sexploitation movie, but it’s all grist for the mill, plus it gives me an excuse to post some delightful ukiyo-e.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non-

Commercial – ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

In the 1960s Japan’s film industry, facing a decline in audiences and competition from television, veered away from producing historical dramas. At the same time laws concerning explicit material were changing, and film studios began producing movies known as pinku eiga (pink films), a genre of quasi-pornographic movies peculiar to Japan. I don’t think porn is an accurate descriptor because unlike most Western pornography there’s an emphasis on drama and narrative, the production values tend to be high, there’s no full frontal nudity, and the sex scenes are simulated. The overall effect is often self-consciously racy rather than erotic, but then I am not a heterosexual male, the target demographic for this type of thing. (Just FYI, Tokugawa Sex Ban contains more boobs than I have ever seen in my entire life.)

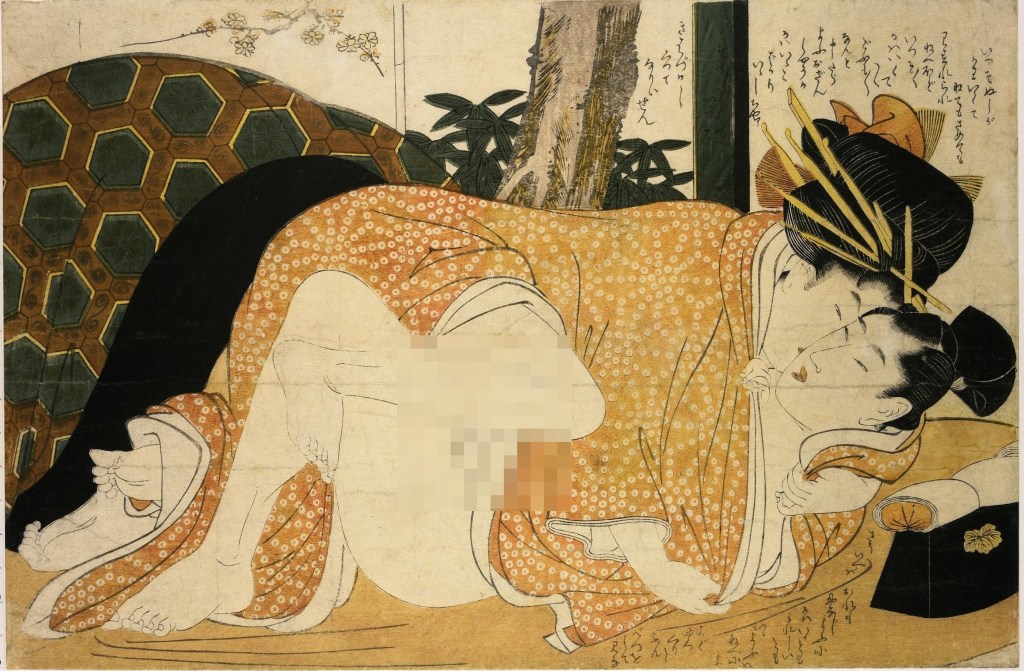

With its legacy of producing period dramas Toei may seem like a mismatch for a soft-core flick. Tokugawa Sex Ban is set in feudal Japan and well within their wheelhouse. The opening credits unfurl with a stylish montage of erotic ukiyo-e prints. These are called shunga. Shunga depict a world free of Judeo-Christian restraints on human sexuality and are typically explicit— way more explicit than this movie— and the artworks accompanying my commentary have been pixelated accordingly. I do this not to spare my readers’ sensibilities (I trust that you are all adults with discerning tastes) but to avoid falling afoul of WordPress’s terms and conditions.

If you’d like to learn more about shunga Taschen recently published a gorgeous collection of erotica by Hokusai and other great ukiyo-e masters, and I highly recommend checking it out if you’re over 18. (If you’re under 18, please stop reading this post immediately.)

In the first quarter of the 19th century the shogun’s ministers are busy arranging marriages for the shogun’s offspring. Given that the shogun has 54 (!) children, this presents a major logistical challenge. When they discuss a match for the shogun’s daughter Princess Kiyo (Miki Sugimoto), the only suitable bachelor they can think of is a rural daimyō in a remote province. One of the ministers points out that the lord in question is reputedly a misogynist.

When we meet Lord Tadateru Ogura (Hiroshi Nawa), he’s not so much a misogynist as an inexperienced man who hasn’t the faintest idea how to please a woman. His wedding night is a disaster. Neither party has a clue what to do, and his young bride recoils from him.

How to remedy this delicate situation? Enter auburn-haired beauty Sandra Julien, who portrays the daughter of a French Catholic missionary (her character is also named Sandra). Sandra has been forced into sexual servitude following her father’s execution. The film introduces her as a plaything delivered to the daimyō inside a box labeled ‘French doll’. Sandra emerges from the box and performs a striptease as Ogura watches. A fiery tango begins to play on the soundtrack, and soon it’s Game On.

This seductive bit of stagecraft is the work of Hakataya Denemon (Fumio Watanabe), Sandra’s sinister pimp. Hakataya could be a character in a novel by the Marquis de Sade. He’s an atheist and an apostate, a former Christian who has renounced his faith. Now he worships only money. Hakataya insists that Sandra follow his example and abandon her belief in God. Sandra is willing to do many things, but she is not willing to do that. Despite the sordid circumstances she has had to endure Sandra retains an innocent child-like quality and a kind heart. As in Sade’s dystopian universe, this marks her for destruction. Of all the women in the movie Sandra is subject to the most extreme abuse.

© Toei Company, Ltd.

After his sultry encounter with Sandra Lord Ogura asks his wife to do the same things in bed that Sandra does. Ogura still has a lot to learn and his approach lacks finesse, to put it mildly. She feels insulted. He feels rejected. They start to quarrel. With a swift kick Princess Kiyo drops him to the floor. (Don’t mess with the shogun’s daughter.)

© Toei Company, Ltd.

Lord Ogura is understandably smitten with Sandra and takes her as his mistress. The daimyō may be something of a doofus but he is actually nice to her, so this represents a significant upgrade in Sandra’s situation. Unfortunately there are complications: Hakataya lurks in the background to remind Sandra who’s boss, and Princess Kiyo’s entourage is outraged that Lord Ogura is consorting with a foreigner. Furious at the blatant disrespect shown to the princess’s status, they attempt to send a message to Princess Kiyo’s father to inform him what’s going on and request that he abolish Lord Ogura’s clan outright. Intrigue ensues. There’s even some brief ninja action, all of it expertly shot and edited.

Princess Kiyo’s minions arrange to have Sandra beaten and thrown into prison. In revenge Lord Ogura orders a ban on all heterosexual activity throughout his domain, which as you might expect does not go over well with the general populace. Anyone found violating the ban is subject to capital punishment. Crowds protest outside the daimyō’s palace. Samurai are developing nosebleeds and married couples are on the brink of armed insurrection. Ogura’s desperate retainers suggest creative solutions to alleviate growing civil unrest including importing beautiful young boys (wakashū) from Edo. A pig with a fancy collar lounges on a cushion as one advisor suggests providing porcine companions. Fortunately this suggestion is not implemented.

A young samurai, Lord Ogura’s friend and retainer Katsuma (Masataka Naruse), helps Sandra escape from prison. A remorseful Princess Kiyo meets with Sandra to ask her advice on how she can win back her husband and end the sex ban which has created so much suffering and unhappiness.

© Toei Company, Ltd.

We see a montage of the two lovely ladies frolicking innocently in various photogenic settings while Sandra Julien sings a syrupy pop song in French on the soundtrack. The entire score is fantastic, ranging from funky 70s grooves to bossa nova.

Events take a dark turn. Sandra falls back into Hakataya’s clutches. He rips her rosary from her, steps on it, and tells her she will have no God or master except him. (Sir, please get over yourself.)

There’s a graphic seppuku scene set to easy listening music. This is not a sentence I ever imagined I would be writing, but here we are.

Sandra contemplates suicide on the edge of a cliff. Katsuma rescues her. They decide to violate the daimyō’s edict together at the palace and face whatever punishment awaits them to repudiate the inhumane sex ban and force Lord Ogura to revoke it. Lord Ogura walks in on them in flagrante. Katsuma pleads with Ogura to spare Sandra’s life before taking his own. As we are about to discover poor Sandra has a more gruesome fate in store for her. She is executed before Ogura can intervene.

Following the loss of his beloved concubine the daimyō finally reconciles with Princess Kiyo. He rescinds the sex ban and order is restored throughout the domain, which experiences an unprecedented population surge nine months later.

According to Tokugawa Sex Ban’s Japanese Wiki entry censors at the time objected to the film’s lesbian content. Rape and torture scenes are apparently green-lit without difficulty, but women engaging in consensual sexual activity with each other is a problem. That’s messed up. (Worth noting is the fact that same-sex relations in Japan were not criminalized during the period in which the film is set.) It’s a pity that the actresses don’t convey more authentic ardor in their scenes together, a common issue in erotica produced by and for men.

At times Tokugawa Sex Ban threatens to collapse under the weight of its own salaciousness. Can a film have too many sex scenes? Turns out that the answer is yes! It’s so well made, however, that it manages to hold your attention throughout. The actors are pros who play it straight no matter how outrageous things get, most of the jokes land, and the director obviously knows what he’s doing.

On the other hand there’s no getting around the premise, which is inherently ludicrous. I assume this is the point, given the text at the end of the film calling out governments for trying to impose restrictions on sexuality and freedom of expression. While I’m on board with not legislating what people do in the bedroom, depicting women (and notably only women) in titillating films in which they are subject to extreme sexual violence is on shakier ground in terms of artistic merit, in my opinion. If you’re going to defend freedom of expression, choose a better hill to die on.

I’m torn on this subject, not least because Sandra Julien appears in a scorching scene in another Japanese film that on the face of it looks pretty rape-y and coercive but which turns out to be a dream sequence. Hiroshi Nawa plays one of the men. He and his companions are inked all over in extravagant tattoos. There’s no dialogue. It’s the best thing in the movie— a movie I will let you discover on your own as I’ve gone on far too long already.

By the way, I enjoyed this more than Ugetsu. Like exponentially more. I’m not sure what that says about me but I thought you should know.

I don’t foresee Tokugawa Sex Ban joining the Criterion Collection anytime soon. It is available on Blu-ray elsewhere.

I love the profusion of patterns and colors in the textiles here. Also this somehow looks cozy and uncomfortable at the same time

Leave a comment