Directed by Kenji Misumi

Because the current is swift,

even though the rapids

blocked by a boulder

are divided, like them, in the end,

we will surely meet, I know.

— Sutoku-in (1119 – 1164) 1

Daiei’s gorgeous production of the classic Japanese ghost story Yotsuya kaidan is an absolute must-see if you are a horror fan and a devotee of samurai cinema. Viewers conversant with the latter genre will find themselves on familiar ground: during the Tokugawa shogunate a group of despicable people meddle in the lives of a samurai’s family, resulting in the murder of an innocent young woman. Her husband single-handedly evens the score.

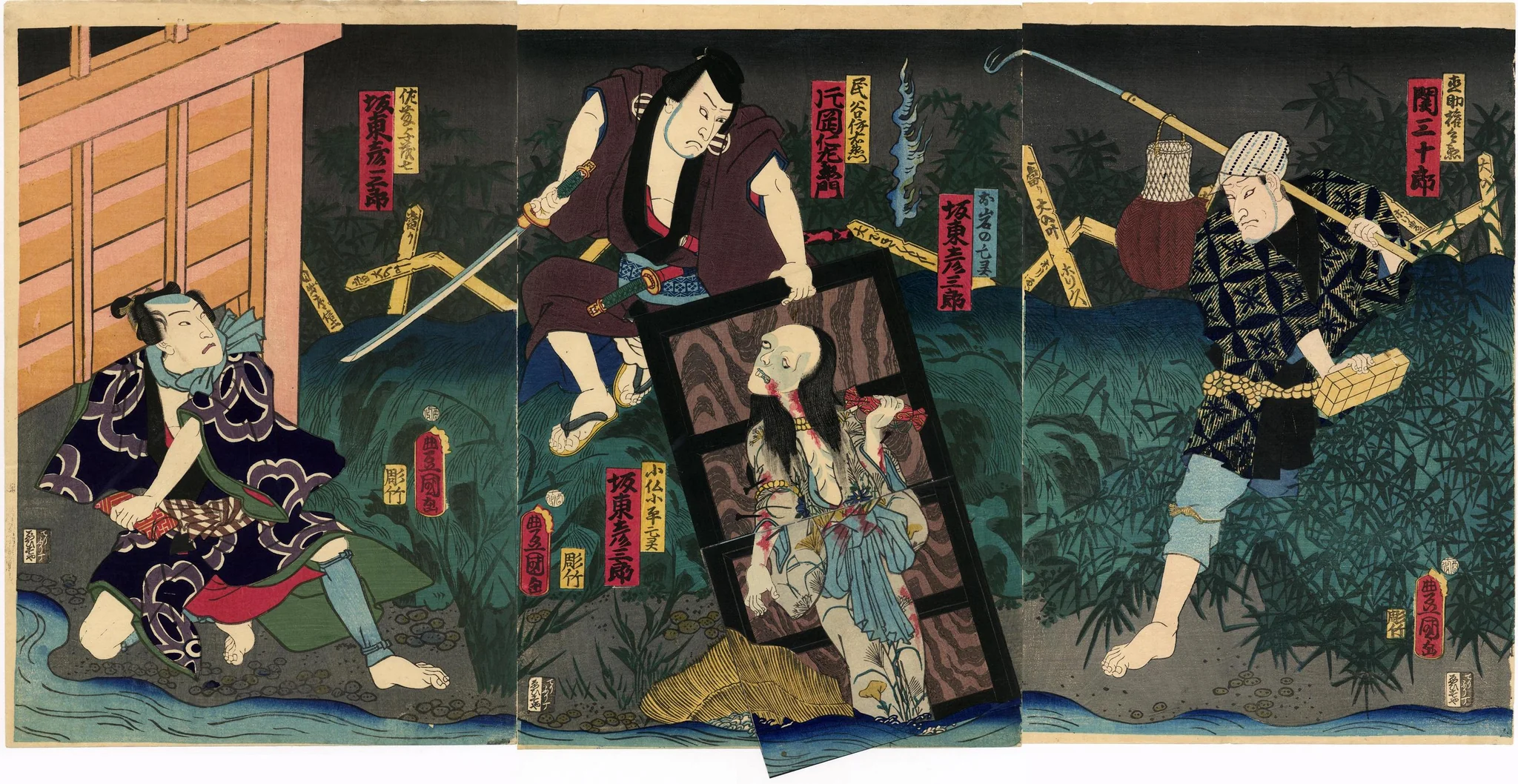

Yotsuya kaidan is based upon the famous Kabuki play Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan (The Ghost Stories of Yotsuya on the Tokaido). A favorite with audiences since its premiere in 1825, the play has been made into more than two dozen films. If you know the play or have seen some of the movies adapted from it you might be perplexed because this iteration of Yotsuya kaidan departs from the story in several key ways. The most significant of these is that it turns the samurai husband Iemon, a hardcore bastard, into the hero. You’re probably thinking that’s not going to work. But work it does, thanks to Kenji Misumi’s tight direction, an excellent script by Fuji Yahiro, and Kazuo Hasegawa’s powerhouse performance as Iemon. Prior to his movie career Hasegawa was a Kabuki actor. He is perfectly at home in the film’s dark world of betrayal and revenge, and moves with a dancer’s grace.

Iemon exemplifies the stock Kabuki character known as iroaku, a handsome villain. These are the sexy ‘bad boys’ of Kabuki whom no woman can resist despite their cruel and often homicidal behavior. In Misumi’s film Iemon is not really evil, but he hasn’t had a complete makeover either. He’s not a great husband. He’s moody and neglects his wife Oiwa (Yasuko Nakada), who is frail and recovering from a miscarriage. The couple are barely getting by financially. Their marriage is a love match rather than an arranged one, however, and Oiwa remains devoted to him. She defends Iemon to his critics, explaining that he is a proud man stuck in a situation not of his own making. Surely that would make any man disagreeable.

Iemon’s predicament is that he is a rōnin, a samurai without a master. In other words, he is unemployed. He assembles umbrellas to make ends meet and spends his leisure time fishing at a canal. Oiwa’s elderly samurai uncle gripes at him to get his act together. Iemon tells him that he has tried repeatedly to find a new position. That requires money and connections; Iemon has neither, and in any event is not the type to curry favor with bureaucrats even if he had the means to do so. This puts him at a disadvantage in Edo, where, as one character puts it, you have to be shameless in order to survive.

Iemon is a skilled fighter and frequently finds himself in demand as a freelance enforcer to settle petty disputes. While this occasionally brings in a little money, it’s the sort of thing that is beneath him as a samurai, and it exposes Iemon and his wife to unsavory characters. There’s no shortage of those in Yotsuya kaidan.

A fight sequence sets the plot in motion. Iemon is drinking at a tavern following his latest unsuccessful attempt at job hunting. Two women, an expensively dressed young lady and her maidservant, rush inside the tavern. A group of drunken samurai is pursuing them. The women take refuge in Iemon’s room. Iemon is inclined to mind his own business until one of the samurai gets in his face. He warns Iemon to stay out of it. These men are the sons of some very important people, people with power and influence.

Iemon does not give a fuck. “Unfortunately for you,” he says, “I’m in a very bad mood today.” This is the cue for an all-out brawl. Iemon cleans house. The lady’s servant asks Iemon how can they ever repay him for rescuing them. Iemon brushes himself off. “I wasn’t really doing it for you,” he says with a smile. “There’s no need to thank me.” As the local badass it’s just another day for him, and he makes his exit.

The young woman is keen to know more about the handsome stranger who came to her aid. She is Oume, daughter of Lord Itō, the nobleman who turned down Iemon’s recent application for a position. Naosuke, a dodgy acquaintance of Iemon’s, informs Oume’s servant that he can help her out and reveals Iemon’s identity to her. Money changes hands and Naosuke arranges a private meeting between Oume and Iemon, which he persuades Iemon to attend by means of a ruse. Iemon is polite to Oume but does not respond to her flirtatious behavior.

Oume’s father scolds her: Iemon is not the sort of man she should be consorting with. She threatens to kill herself. Lord Itō tries to placate her by inviting Iemon to his estate, ostensibly to thank him for helping his daughter at the tavern. In reality it’s another manipulative attempt to throw Iemon and Oume together in the hope that he will leave his wife for her.

It’s obvious to everyone that that is not going to happen. Iemon’s not interested, but he’s reluctant to offend Oume because of who her father is. There’s still a chance he might get a job out of this mess. Iemon’s least objectionable option is to avail himself of his host’s hospitality and get drunk. “If you didn’t have a wife,” Oume asks him, “would you care for me alone? Could we be together then?”

Oiwa knows nothing of the machinations taking place behind the scenes to break up her marriage. She believes that Iemon’s visit with Lord Itō is the opportunity to improve their situation that they have waited so long for. Maybe things are finally starting to turn around.

Things are about to get worse. Much worse.

Oiwa is struggling to recover from her miscarriage. She needs a specific type of herbal medicine, but it is a costly import from China, and neither she nor her husband can afford it. The medication is a crucial plot point, and from this moment on the film shifts from domestic melodrama to horror in somber doom-laden style. Yukimasa Makita’s spectacular Fujicolor photography imparts an otherworldly gloom to every shot. The lonely canal where Iemon goes fishing is genuinely spooky and becomes increasingly nightmarish as Yotsuya kaidan nears its tragic conclusion.

Yasuko Nakada is heartbreaking as Oiwa, capturing the anxiety and vulnerability of a woman who has lost a child and fears losing her husband as well. Iemon doesn’t deserve her but redeems himself in the film’s last act, where he exacts his revenge. If you are only familiar with Hasegawa from the gentle character he portrayed in Mizoguchi’s 1954 film Chikamatsu monogatari you are in for a shock. He cuts a swath through the bad guys in this like a harvesting machine. His rage is so all-consuming that Iemon is in danger of becoming an onryō (vengeful ghost) himself. Yotsuya kaidan bestows mercy upon him at the very end in a scene that is as beautiful as it is eerie.

The real horror of Yotsuya kaidan has nothing to do with the supernatural. The film depicts Edo as a sordid world corrupted by greed and self-interest. Life is cheap there: innocent people end up at the bottom of a swampy canal simply because they got in the way of someone above them on the feudal food chain. Nothing good can survive in such a place. Oiwa and her beloved Iemon are better off elsewhere.

- Mostow, Joshua S. (2023). Pictures of the Heart: The Hyakunin Isshu in Word and Image. University of Hawai’i Press. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Jigokumon (Gate of Hell) (1953) – Ukiyo-e Owl Cancel reply